Britain is not Germany

Cultural critics trained in Frankfurt School political criticism are accustomed to borrowing theatrical metaphors of spectacle to talk about the uses to which visual media have been put for the ends of politics in the modern world. Metaphors of theater appropriately characterize the exploitation of aesthetics for the use of politics so contrary to the hopes of political Enlightenment, the dominant relationship of political players to quiet masses, and the silencing of dissent. But I believe that we are seriously in error when we hold the model of Weimar Germany, in the midst of which the Frankfurt School critique was formed, as the only way in which political power or injustice exerts itself. I have carefully plied apart the notion of spectacle from the conceit of the common experience in order to make room for other kinds of power dynamics, other kinds of exclusions than those beaming down from a single, glaring force.

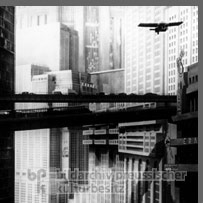

Pictures of cities and the everyday landscape, like the films of life in Weimar Berlin used by Kracauer to discuss spectacle in Germany, tell individuals how to look at themselves in their surroundings. They comment on the fabric of every-day life: on what appropriate interactions with strangers look like, on how to interpret the face one meets in the crowd. In mid-eighteenth century Britain the technology for creating this kind of commentary was held by a small elite. By the 1780s it was coming into the hands of a burgeoning middle class, and by the 1830s it was reaching a broader audience still. The spread of technology from the elite down did not mean that the politics of the elite were able to impact the mind of the proletariat a century later. But it did mean that certain conventions about showing the landscape persisted with remarkable tenacity. In particular, the elite’s sense of social cohesion, their ideal of an ancient England knit together by feudal dependence, this stayed: it fed the myth of civil society that the middle class wove about itself; its conventions were easily read; it ultimately fed the political agendas of politicians who made sure that it was disseminated.

Like the Frankfurt School theorists, I too have a story about the exclusion of particular social groups, the building of a nation, and visual technology. But in nineteenth-century Britain, no power cabal suddenly swooped into power. In my story, the creation of a common experience happened separately several generations before the creation of a national identity for which common experiences were later exploited. As transportation technology propelled certain groups into control, these groups excluded others from power. Visual technology encouraged a sense of belonging to such a group, and encouraged indulgence in paranoid fantasies about those who lived differently.

Only much later did high politics intervene, in the form of propaganda and urban renewal deliberately constructed to undermine the divisions between social groups. In the end, political manipulation would exploit a period of war, famine, riot, and fear, to the end of a unified social body. It would capitalize on thirty years of habituation to looking at oneself enjoying a common experience. All this happened only in the wake of the creation of an idea that such mutual accountability could exist, and already after major groups had already been excluded from that idea.

(the above posts from an essay in progress)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home