Staging the modern

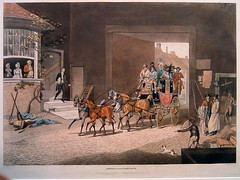

A chaise became a stagecoach when it stopped to set down passengers at a resting place like a familiar inn. The place was called a stage because it allowed the passengers to promenade while they took the air, to see each other, and to be watched by the local villagers. A stagecoach went from watching point to watching point. That use of the word in English originates in the early seventeenth century with the very earliest appearances of coach stops and inns.

By the nineteenth century, the golden era of the stagecoach, the middle class became familiarized with the experience of travel for the first time. As stagecoaches ran more reliably and frequently, the vehicle and not the place became characterized as the stage, the place of excitement and exhibition. On a gentler stagecoach running a smoother road, one could sit atop and gaze upon the landscape while being seen by others.

Traveling by stage was so familiar that the word was borrowed to describe any kind of general process or progress that obeyed an orderly sequence. A disease passed through stages. Geological time flowed in stages. Now, each man could talk about himself as passing through rites of passage characterized by experiences and subjective processes common to all: he could talk about going through stages.

Other authors have characterized the way this shift in self happened, the way identity came to be defined as a subjective, private source of self as positioned between solid categories of experience common to great numbers of individuals.

My aims are neither so grand nor so psychological. But I do want to know what happened to the experience of landscape, of the public, of interacting with strangers, as a nation began circulating together and exchanging its ideas. As this anecdote suggests, circulation created a common experience, the sense of “going through stages” that anyone else might know about.

Traveling individuals knew that they passed through worlds that other members of the nation had experienced. But as the etymological investigation makes clear, a world characterized by “stages” was not necessarily a world with a central place where people read their identity together. The English stopped referring to inns as theaters or stages, indicating that no single inn need be familiar to everyone. The relative inconsequence of the promenade and people-watching at any given inn was only too obvious to anyone who had come to think about all the other villages and cities to which a modern stagecoach was going.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home