The Ballad of Meriwether Lewis and Esmeralda Biggott

A short farce in one act

[Boy and girl are sitting at a café.]

Boy: what’s that you’ve got there?

Girl: huh?

Boy: I said, that looks like a map.

Girl: it is a map.

Boy: hey, that looks like a real honest-to-god atlas!

Girl: (annoyed) so what if it is?

Boy: you know I work with maps too…

Girl: (patronizingly) All right. You work with maps. What kind of maps would those be.

Boy: well I just came back from the Pacific territory,

Girl: ::stares::

Boy: and right here in my messenger bag I have our draft

Girl: Give me that!

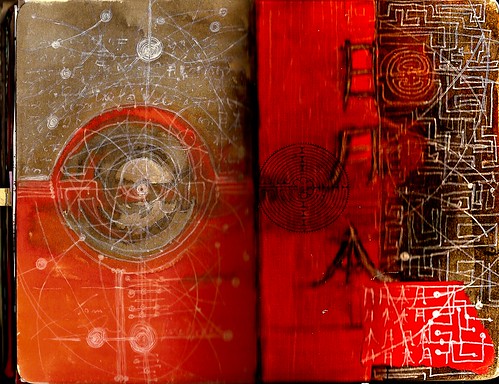

[looks at map, which looks like it has been executed in crayon]

how did you end up working on this project? This was going to be my project!

Boy: Well, President Jefferson and the body that would one day become the Army Corps of Engineers sent me, I’m actually not a cartographer, not like you anyway…

Girl: you’ve ruined everything! these are incredibly imprecise calculations too. You’ve stolen my idea and you’ve made a hack out of it.

Boy: but I didn’t know, it wasn’t my idea to go,

Girl: I can’t believe I didn’t know about this project.

Boy: I could tell you about it,

Later

[Boy and girl have been kissing on a bench

The girl turns away and stands up]

Girl: I don’t know about this

Boy: what’s there to – I just hoped it would make you happy

Girl: what makes you think that you should even be here?

Boy: but I think I like you, I saw you,

Girl: we don’t even have anything in common.

Boy: but the café, the map, I thought

Girl: lots of people like maps. You don’t know anything about me.

Boy: how many girls even know how to read a map?

Girl: I’m not the first one in the history of the world.

Boy: look I may not have a fancy education like you but at least I’ve been some places. I’ve actually explored the areas, not just plotted them on a piece of paper so that they could become useless in some library where nobody but old farts would ever look at them

Girl: ::silent::

Boy: I could have had lots of girls, I’m choosing you because I think you’re special. I looked first so I saw it first. You haven’t seen how special I am, but I can see how special you are, so I’m here, and you ought to look at that.

Girl: I’m looking and I’m not seeing anything

Boy: ::silent::

Girl: I didn’t mean it like that

Oh God, I’m sorry.

Boy: never mind.

Let’s talk about something else.

Did you ever hear the joke about the cormorant?

Girl: Meriwether, sometimes people just aren’t right for each other.

You seem like a fine catch and all. Maybe I’m just not attracted to you.

Boy: ::silent::

Okay, I’m going out for a walk.

Later

[A kitchen. Boy and girl have been cooking.]

Girl: You still seem down. What’s wrong with you anyhow? Why aren’t you happy?

Boy: I’m just not doing well, okay?

Girl: Most boys when they’re after a girl are all sunshine and happiness. I don’t know why you think gloom is a strategy for success.

Boy: I’m thirty-one and I’m a complete failure. What have I accomplished?

Girl: but you found the Northwest Passage! Explorers have been looking for centuries…

Boy: there is no Northwest Passage. I proved that there is no Northwest Passage. Thanks to me the world is at least ten percent less glamorous, less of a wilderness, and less full of possibility than it was before. I mean think about it. I was the first to pave this way into the great Pacific Northwest, and when millions of white people start following the path I laid out, they’ll strip the wilderness bare, kill all the buffalo, and poison the native population. Some great endeavor.

Girl: but you went to all these unknown territories. You know first hand what I only know about in theory.

Boy: You could have made up all the coordinates just as well without me. You were doing it anyway.

Girl: but the map will be so much better with your data

Boy: anybody could shovel in more data. A freaking computer could’ve done what I did.

Girl: but we don’t have computers yet!

Boy: then you could’ve gotten yourself another explorer. The US Army could’ve gotten itself ten other explorers.

Girl: but I’m doing this for all of us. Maps are something we do together. One person explores and the rest find out. We all celebrate together. It’s an accomplishment. You could become a national hero. You represent everything we think an American should be

Boy: some celebration. If I’d broken my neck at Missouri Falls no one would have shed a single tear.

Girl: the eggs are burning.

Boy: I’m not hungry any more.

Girl: would you help me with the darn eggs.

Boy: You do something about the eggs. I’m not hungry.

Later

They are chatting by phone. They are looking for the same point on each of their maps.

“Do you see the place between the Columbia River and Haystack Rock that looks like the snout of a Boar?”

“It looks like the nose of a lion to me”

“No, that’s the bay one dip to the north”

“I think you’re looking at the wrong place.”

“I don’t know what I’m looking at.”

“So look at Haystack Rock, and then count one, two, three bays to the north.”

“Got it.”

“See? It doesn’t have a name yet.”

“I will call it Esmeralda Cove, after you.”

“I’m putting it down as Cape Disappointment.”

“Because I’m so disappointing?”

“Because I’m in a state of disappointment.”

“Why on earth are you a disappointment?”

“Because I’m disappointed that I can’t even make a map by myself. I needed someone else to help me with it.”

“That’s not being a disappointment. That’s just getting along well with other children.”

“I just don’t want you to be disappointed in me when you find out what I’m like.”

“Well don’t get your hopes up, I’m not planning to.”

“Get to know me?”

“Be disappointed.”

“Cape Disappointment looks like a nice bay. I’d like to go there one day.”

“Maybe you will.”

“Maybe you’ll take me.”

“Maybe I will.”

We see that they are actually looking at two different bays entirely.

Later

[Boy and girl enter slamming a door behind them]

Boy: You think you’re so hot. I could have gotten any girl in the world and here you are on your high horse

Girl: Yeah, who told you that, some barmaid?

Boy: Um, yes…

Girl: Then good luck with your barmaid

Boy: Only the sexiest barmaid in all of San Francisco where the girl-boy ratio is one to twenty (muttering) and after she kneed Clark she held my hand and said I could have had any girl in the world. (aloud) It doesn’t matter I’m just saying, you think you’re such a catch. But maybe you’re just missing what’s in front of you.

Girl: I suppose you had dozen of Indian lovers too

Boy: as a matter of fact

Girl: that’s disgusting

Boy: Don’t say that! You’re such a bigot.

Girl: But they’re dirty and brown.

Boy: let’s not talk about it, okay?

Girl: What did you do, become engaged to an Indian chieftess?

Boy: She was a chieftan’s sister, not a chieftess. They have medicine women, but not chieftesses.

Also she was married when we met, so we couldn’t become engaged.

Girl: oh my God, you’re talking about Bird-woman, aren’t you? Wasn’t she the alcoholic’s wife?

Boy: I don’t think I want to talk about this any more.

Girl: that’s so crazy. Nobody had any idea that you were in love with Bird-woman. Really, the whole trip?

Boy: Look, I’m sorry I brought it up. Can we please change the subject?

Girl: Well tell me about her

Boy: did I ever tell you about when we shot the first cormorant?

Later

[Girl is crying]

Boy: I didn’t want things to end up this way

Girl: but you ruined everything. My career is ruined because of you. And now you’re famous and I’m a disaster. And now you’re leaving.

Boy: I’m not leaving. I’m just different. Anyway it wasn’t my plan, it’s not like I planned this.

Girl: you don’t even know what you want. You never know what you want.

Boy: look, it seemed like a good idea at the time. Cute boy, cute girl. It seemed like it should work on paper. It just didn’t work out.

Girl: ::sobbing silently::

Boy: do you want anything? Can I tell you a joke or something to cheer you up?

Girl: ::sobbing::

Boy: ::silent::

Oh for Pete’s sake. You aren’t even trying.

Girl: ::blows her nose:: anyway forget you and your stupid I-could-have-any-girl-in-the-world adventure stories. That’s one thing. The map’s another thing. How dare you ruin my career.

Boy: What do you mean? It’s not my fault. It’s not like I tried to ruin your career.

Girl: of course you planned it. You plan everything. You’re a cartographer.

Boy: stop it. Stop it! What do you even want from me?

Girl: I just wanted another cartographer to talk to. And now you’re doing the project I wanted to do, and you’re doing it without me.

Boy: pull yourself together. Only you can be responsible for yourself.

Girl: I can’t do it alone. What do I know? I’ve never even been anywhere. I just put the points on paper. You’re the explorer. I just write down what you tell me.

Boy: I tried to tell you things. I tried to tell you everything. I tried to warn you.

Girl: that you broke girls’ hearts. You didn’t warn me that you ruined their careers and stole their maps. I didn’t ask to have your babies, I just wanted to make a map with you.

Boy: but that’s what we did

Girl: until you stopped working on it with me and started working on your own without telling me and then I didn’t have a map of my own any more

Boy: but we had fun while it lasted

Girl: and then you stopped having fun on me

Boy: Like you didn’t want it.

Girl: Now they’re saying that my map is wrong. Sailors are getting killed every time they try to sail up the mouth of the Columbia River; their boats get wrecked on the sand bars. They’re blaming everything on me.

Boy: that’s not my fault. I measured everything as well as I could.

Girl: I thought we had so much in common, I thought things were going to work out

Boy: it turns out we don’t really get each other at all, do we?

Girl: but you told me

Boy: a lot of things. I guess I said a lot of things

Girl: lied to me. you lied from the very beginning

Boy: I didn’t know what was going on then. I didn’t know what you were like. I didn’t know that you weren’t everything I wanted.

Girl: what I’m like. do you know now?

Boy: you’re not everything I ever wanted.

Girl: do you know what’s going on now?

Boy: how would I, how would I know if I knew?

Girl: do you know somebody else, who else would know?

Boy: know what? I don’t even know who you are

Girl: you were, you’re the one who wanted me

Boy: I am, I don’t even know who I am.

Later

[boy is standing in the shadows. We can only see his feet.]

Boy: I came like you asked. If you want to talk to me, talk to me.

Girl: why are you standing in the shadows? I can’t see your face

Boy: I like it in the shadows.

Girl: come out and talk to me. you’re acting like a child.

Boy: you never even gave me a chance, you never even tried to get to know me.

Girl: but I wanted to, I just

Boy: maybe we’re just not right for each other. Can’t you just accept that we’re not right for each other?

Girl: but you don’t even know me

Boy: I guess that’s right

Girl: but I want you to know me!

Boy: I’ve been here and I’ve had people try to change my mind on things like this before and it’s never worked out. I’m not going to have my mind changed.

Girl: you’re just saying that because you’re afraid of being wrong, you’re afraid that you don’t have all the answers, and you’re not even willing to go deeper to find out the answers. As if finding out how much we had in common were scarier than all the Cheyenne scalping parties put together.

Boy: I’m saying that because I’m telling you where I’m going

Girl: you’re afraid of dating another cartographer. You’re afraid you might have to compete with her. You’re afraid of having your readings challenged. You won’t risk learning something new from her, because you’re just too scared of not being Mr. Manly Adventurer all the time.

Boy: I just don’t want to be with you. At least right now. Okay? This is 1806 and we haven’t even invented second-wave feminism yet.

Girl: but we had so much in common. You like maps; I like maps, you like –

Boy: but you never really know the depth of landscape from a map.

Girl: but we were had just started looking

Boy: I’ve made up my mind

Girl: looking at it together

Boy: you never really looked close enough at me

Girl: but we were trying together. Trying’s just like a map, you try plotting things out

You add one little bit of information and then another bit, we were going to keep plotting and learning --

Boy: I’ve had it with maps. I’m going to invent another kind of map entirely, a map that’s going to go dark in all the regions where the trail disappears or the fields get covered in shadows from the passes.

Girl: what good would that do?

Boy: it’d give people more realistic expectations, for a start. People think that just because you can send an explorer out you can learn everything there is to learn about the wilderness.

Girl: I don’t even know what you’re talking about.

Boy: And then it turns out you don’t know anything about wilderness. You know where the points are and you get confident. That’s why your sailors are dying. A map can’t tell you where the sands are. We had guides who grew up there. The map just makes you over-confident and then all these East Coast boys sail in fast and their ship gets rafted and they blame you, Esmeralda. It’s not your fault. It’s the same with the human heart. People think you can learn everything there is to know. I don’t even know where the passes are in my own heart. How the heck am I supposed to tell other people about it?

Girl: you asked me where I was coming from, I just wanted to

Boy: It’s only safe where things haven’t been mapped. I don’t want anyone to know where I am.

Girl: but you told me

Boy: I’m through with telling people where I’ve been. I’m going to invent a kind of map that eats itself.

Girl: but you gave me a map, you told me, I thought… together…

Boy: ::walking away:;

Technorati Tags:

meriwether lewis,

lewis and clark,

one-act plays,

fiction,

farce,

satire,

cartography,

maps,

mapping,

gis,

oregon,

history,

america,

wilderness,

american history,

exploration,

love,

isolation,

loneliness,

breaking up,

miscommunication,

feminism,

women,

sex,

landscape,

expertise,

cormorants,

cormorant jokes